What fictional forms were the precursors to mystery stories? Many point to Edgar Allan Poe’s (1809-1849) work, especially his August Dupin short stories. While his influence is huge, there’s more to the origins of the modern mystery. Let’s look at another contributing genre:

Victorian Sensation Fiction

Critics agree that Victorian sensation fiction (approx. 1850s to 1880s) was an ancestor of modern detective fiction, too. The characteristics of the genre and its overwhelming popularity at the time were fostered by several factors:

1. Poe’s short stories, which took a few decades to make its influence felt.

2. People’s interest in crime. Many plots for sensation novels were taken from well-known cases of bigamy, swindling, and murder.

3. The institution of the Metropolitan Police Act of 1829, with the resulting police force being very much in the public eye. If you’re interested in the fascinating details, check out my earlier post about it.

4. The increase in literacy and affordability of serial magazines, where a great many short stories and novels (in chapter installments) were published.

5. The proliferation of newsheets and newspapers.

6. The growing affluence of the middle class, as trade and industry increased with the ever-growing British empire.

7. The emerging faith in science and medicine to penetrate the mysteries and problems of life.

Sensation fiction used crime, secrecy and deception as the means to produce what the reviewers at the time termed “sensation” – a very body-focused reaction, where the plot is designed to make the reader feel the fear, excitement, suspense, etc, through the sensations experienced by the main character(s).

As an illustration, let’s take a closer look at one short story in particular.

Sheridan LeFanu’s “The Murdered Cousin” (1851)

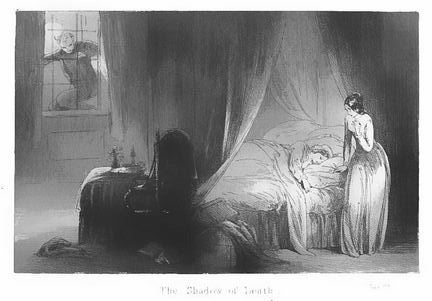

“The Murdered Cousin” is a terrific example of Victorian sensation fiction: the wicked uncle, the puzzle of the locked room; a heroine in danger, a once-grand estate in ruins.

J. Sheridan LeFanu, an Anglo-Irish writer of the nineteenth century, wrote both novels and short fiction, dealing with crime, mystery, and ghost stories. His best known works are Uncle Silas, Carmilla, and The House by the Churchyard. He was also an early practitioner of the “locked room” style of mystery, originated by Edgar Allan Poe.

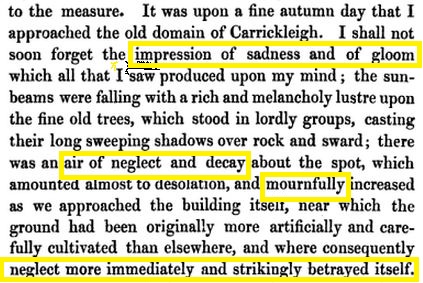

“The Murdered Cousin” is earlier along the sensation fiction continuum, and retains more of the gothic-style of sensation: evil sinister castles and strange bumps in the night. Victorian sensation fiction later moved away from the gothic, shifting the thrill from castle gate to the ordinary doorstep. The Poe influences, in both the violence in the plot and the crumbling estate setting, are very “Fall of the House of Usher” in style. There is an emphasis on physical details to create terror and suspense.

Here are a few excerpts to illustrate features of the story, with a reflection following each one. Further down is a link to the entire story, through Project Gutenberg.

First person point of view:

Many Victorian sensation stories were told in the first person, through “confessions,” letters, and so on, with coy aliases or initials to “protect” the individual, as if it were a true story. The goal was an increased reader identification with the protagonist. First-person perspective/eyewitness accounts were meant to duplicate the sense of “true crime” accounts which were reported in newspapers and court transcriptions, widely distributed at the time.

The aristocracy:

You can see that the estate is portrayed as decaying, run-down, neglected. The author intends to reflect the moral and economic conditions of the aristocratic villains of the story. However, it also reflects the general view held by middle-class readers of the time. While the aristocracy was respected as a whole, and still enjoyed a great deal of power (in Parliament, for example) and prestige, the upwardly-mobile and increasingly prosperous middle class saw the aristocracy as the lingering remnants of an old feudal system, decaying, losing power, corrupt, immoral. Certainly, aristocratic families were experiencing economic difficulties and middle class/upper class intermarriages were becoming more frequent.

LeFanu, a man of the middle class (most sensation fiction writers were), often depicted a decaying upper class – if not corrupt, then debilitated. He wasn’t the only writer of the time to do so: Wilkie Collins, a very successful sensation author and associate of Charles Dickens, also featured depraved or ineffectual aristocratic characters in his stories.

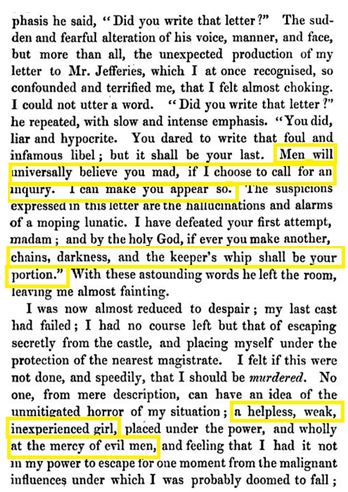

The vulnerability of women:

As a bit of story background here, the protagonist’s uncle is in desperate need of funds, and she is at his mercy, being orphaned and given into his care through her father’s will. The uncle tries to bully her into marriage with his son, makes oblique threats when she refuses, and keeps her isolated from potential allies. When she writes to someone for help, he intercepts it, of course.

Underage, married and even divorced women could not own property, nor did they have the legal power to manage their own affairs. The threat of incarceration in an insane asylum was a very real one – it only required the signature of two examining doctors and could be easily procured. Victorian readers felt conflicted about insane asylums: they feared lunatics running around unconfined, but also were horrified by the idea of a sane person unjustly shut up among the insane.

Want to see how she escapes? Read the entire story here:

Online Reader – Project Gutenberg.

Have you read any Victorian sensation fiction? Do you think Victorian literature can still hold its appeal today, or are we too far removed from the time, with better options to replace the old stories? I’d love to hear from you.

Until next time,

Kathy

Love Poe! And, apparently, I also love sensational fiction, although until today I didn’t have a term for it. The thing that has always attracted me to Poe and others similar to him is the visceral nature of the writing. Your stomach twists. Nerves shudder. One feels the ever-present doom.

Excellent post!

Thanks, Gene! This was my area of specialty in my scholar days. Loved delving into sensation fiction!

Great post. I didn’t know this had an actual name. I read a lot of this type of fiction during my university English courses and it was such a relief for me from some of the more lauded works of fiction that I didn’t enjoy. I’ll have to check out the rest of this story.

There is something so wrong about “lauded” works being a trial to get through, don’t you think Marcy? Glad that sensation fiction was there to “save the day”!

Sounds like a good story! I love those old gothic novels. I have not heard of this one.

Patricia Rickrode

w/a Jansen Schmidt

And this one is actually a short story, so there isn’t the big time commitment! Hope you get a chance to read it, and thanks so much for stopping by. 😀

This is so cool.

The scholarship of your pieces is so impeccable. I make up everything I write and still get stuff wrong.

Your use of clippings is especially interesting. Great work, K. B.

Aww, thank you, Perry! None of your stuff seems made up to me!

Fascinating stories, Kath! You really know your stuff.

This characteristic really caught my attention: “The emerging faith in science and medicine to penetrate the mysteries and problems of life.” Interesting to consider how an emerging awareness of science affected public taste in literature.

Thank you, Paul! This is part of why I love the Victorian period. Such an exciting, dynamic time.

Amazing. I had no idea. And you know, I do think they could still hold appeal today. A good story is a good story. I am totally intrigued!

Thanks, Nat! Sometimes the old style is new! 🙂

It’s fascinating to see the progression of mysteries. I was recently telling my son about which Poe stories were my favorites (not Tell-Tale Heart) and encouraging him to read them. I’m curious about how tales like The Invisible Man, Dracula, and even Frankenstein relate to the spooky and secret sensationalism that mysteries eventually entailed. I don’t really know much about Victorian sensation fiction. Intriguing post!

So glad you liked it, Julie! The Invisible Man and Frankenstein are definitely more science-grounded, with themes about Man’s hubris/ambition getting out of hand through disastrous tinkering with the mysteries of nature. Dracula is more simply sensation/horror, I think. Just my humble opinion. There’s also Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Thanks for stopping by!

Ah – shades of Elizabeth Gaskill!